Rubato, and how to get there from “Gray Day”

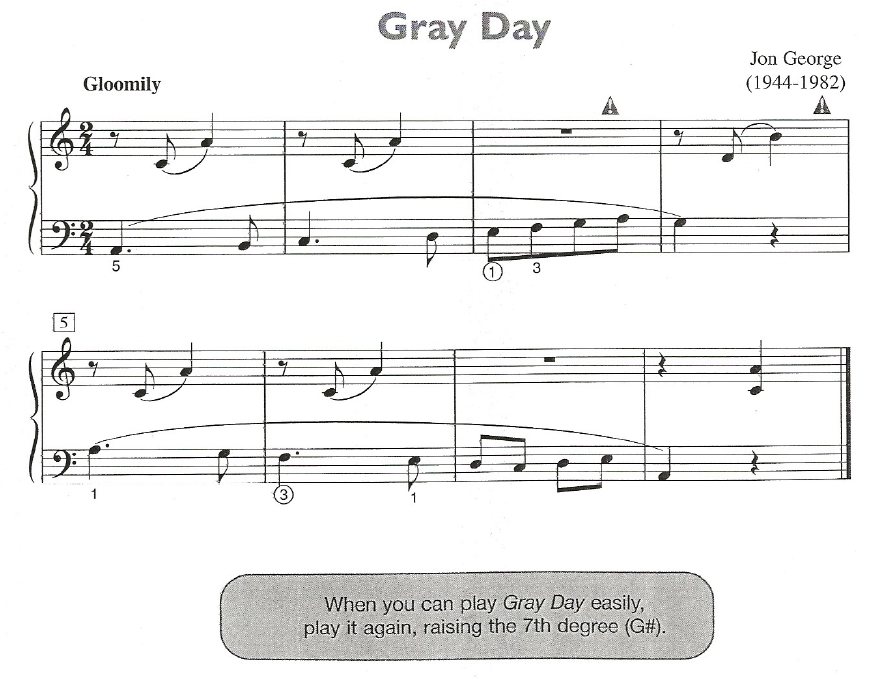

You can find Jon George’s “Gray Day” in The Music Tree, Part 3 (Clark, Goss, Holland; Alfred pub.), on pg. 19.

Before we even get started, let me address your raised eyebrows. Is this really where I’m going to begin a discussion of rubato? The answer is no. I started a discussion about rubato with this student years ago.

By the time a student reaches “Gray Day,” I would have been planting the seeds of that discussion for years, with pieces such as “Bedtime,” from Time to Begin; “Horseback Riding,” from the Faber Performance (FP) Primer; “Bubbles,” from Music Tree (MT) 1; “The Handbell Choir,” from FB 1; “Folk Song,” from MT 2A; “Home on the Range,” from FP 2A; “The Wind beneath My Wings,” from MT 2B, “A Day at the Carnival,” from FP 2B, and many others. I realize that this sounds absurd; rubato is an advanced technique. How could I be addressing it in elementary lessons? Let me take you through “Gray Day,” to show you how I’m planting those seeds.

From a pedagogical standpoint, one of the most important things about “Gray Day” is the length of the two LH slurs.

These, of course, aren’t the first slurs that this student has encountered. Several years ago, when slurs were introduced, I explained that each slur needs three critical ingredients in addition to legato:

- One of the notes is more important than the other(s). It’s the Queen of notes. The King of notes. It is the coach, and all the other notes are the team. It’s Beyoncé and all the other notes are her Beyhive. This phrase goal, not matter what you call it, receives a royal accent.

- The last note of the slur is soft.

- End the slur with a breath.

This is a simplistic set of guidelines that doesn’t acknowledge any nuances and exceptions, but it does represent the essence of what a slur conveys and it presents an appropriate challenge for a child. It could be a year before that child is ready to develop these guidelines further; the place I like to start that development is by getting from the goal to the end of the slur via a diminuendo. Only after that’s mastered do we begin to sneak into a phrase and crescendo toward its goal.

In the earliest slur – a two-note slur – the first note is the goal. Once slurs grow longer, I choose the goal for the student. As I do, I explain my reasoning to them: the highest note, the note on the downbeat. There are other ways to choose goals, but these two work beautifully and cover almost every circumstance a young pianist will face. Developments of and exceptions to these guidelines come along slowly, as the music the student studies becomes more complex, and as this happens, I will have them participate in and eventually take over this kind of decision-making. In the analysis below, I’ve circled the phrase goals (which is exactly what I’d ask the student to do in their score.)

All of that has been going on up to the point of “Gray Day.” What’s new, as I said, is the long slurs. The student likely needs a strategy for four-measure-long crescendos and diminuendos. I provide that to them by laying out all the dynamics that they know, as a series of steps. Because I think of crescendos as exponential, I’ve crowded the dynamic markings toward the end of the crescendo marking. But I think of diminuendos in more of a linear fashion, so I’ve spaced the dynamics out accordingly.

One last bit of pedagogy: I always ask my students to do something – one thing – that isn’t explicitly written in the score … something that goes beyond our current requirements. I call this “gold medal thinking.” For that, I’d ask them to work on the balance between the hands. That’s not a new concept for this student, but the LH doesn’t often get the melody, so we rarely get a chance to balance LH over RH.

At this point, I’d be ready to move on to something new.

The student has two choices about how to proceed: they can put the piece away, or they can move it to their playlist. As long as it remains on the playlist, I might hear it at any lesson, or I might not – regardless, they have to be always ready to play it. I put the playlist to a variety of uses:

- It gives me an easy, positive way of starting out or ending a lesson

- It can provide a way of lightening up the lesson if the student needs it

- It also offers me opportunities to “foreshadow,” which is the term I use to describe experiential “previews” of ideas that I see down the road for this student

One of the ideas worth foreshadowing in “Gray Day” is that of climax – meaning the one, single moment in the piece that signals the central highpoint. This consists of elevating one of the phrase goals to a higher status: King of Kings. My instincts lead me toward the goal in m5. If had to tie that decision to the score, I’d say that m5’s goal is higher in pitch, that climaxes tend to come later rather than earlier, and that m5’s goal happens to be tonic. The latter reason is even more compelling when you raise the leading tone (as the directions suggest).

All this while, as we’ve been discussing sound and form, we’ve been laying the groundwork for rubato.

In fact, our analysis of this is piece is a rubato map. To execute it, you simply need to lean toward the first goal exponentially, just as the dynamic plan suggests, push through it toward the climax, and then slowly wind your way down to the end by way of a gradual ritardando.

Would I suggest this rubato to a “Gray Day” student? No. At least that’s what the orderly, logical part of me says. Rubato is a long way off for this student. But the more organic, more artistic side of me isn’t quite sold on that “no.” The “ritardando” side of that rubato, perhaps if delayed until the final two measures, is well within the student’s grasp. In addition, that part of me suggests that the reason for not teaching a full-on rubato isn’t about it being far off as much as it is about mastery of the current tasks. How satisfied am I with the student’s ability to understand the sound that this piece demands and mastery of the technique required to produce it? Tone production, emphasis, crescendo, diminuendo, balance, legato, ritardando … chances are that this student has more than enough challenge among these things.

In the end, what has “Gray Day” taught the student about rubato?

- Music must be interpreted. The markings on the page are only half of what needs to be done.

- Phrases have goals.

- Pieces have goals.

- We approach goals exponentially and move away from them in a linear fashion.

- We’ve worked with one half of rubato: ritardando.

When the day comes that this student is ready to use a full-fledged rubato, they will have had years of experience laying a groundwork that will form that rubato. They will understand where to use it, how to use it, and why they’re using it.